5 Types of Music Distribution Companies

First of, let’s get one thing straight. “Distributor” is not a specific type of company — it’s a role that can be internalized by other parts of the recording chain. The prime example is the major labels:

1. Major Distributors

The majors are perhaps the only players on the recording market that own a catalog big enough to negotiate on par with prominent DSPs and get direct access to their editorial teams. So, they don’t really need distribution partners — the label’s distribution department works 99% of the catalog. In fact, one could argue that this very ability to distribute music globally through direct DSP licensing deals is what turns a label into the major these days.

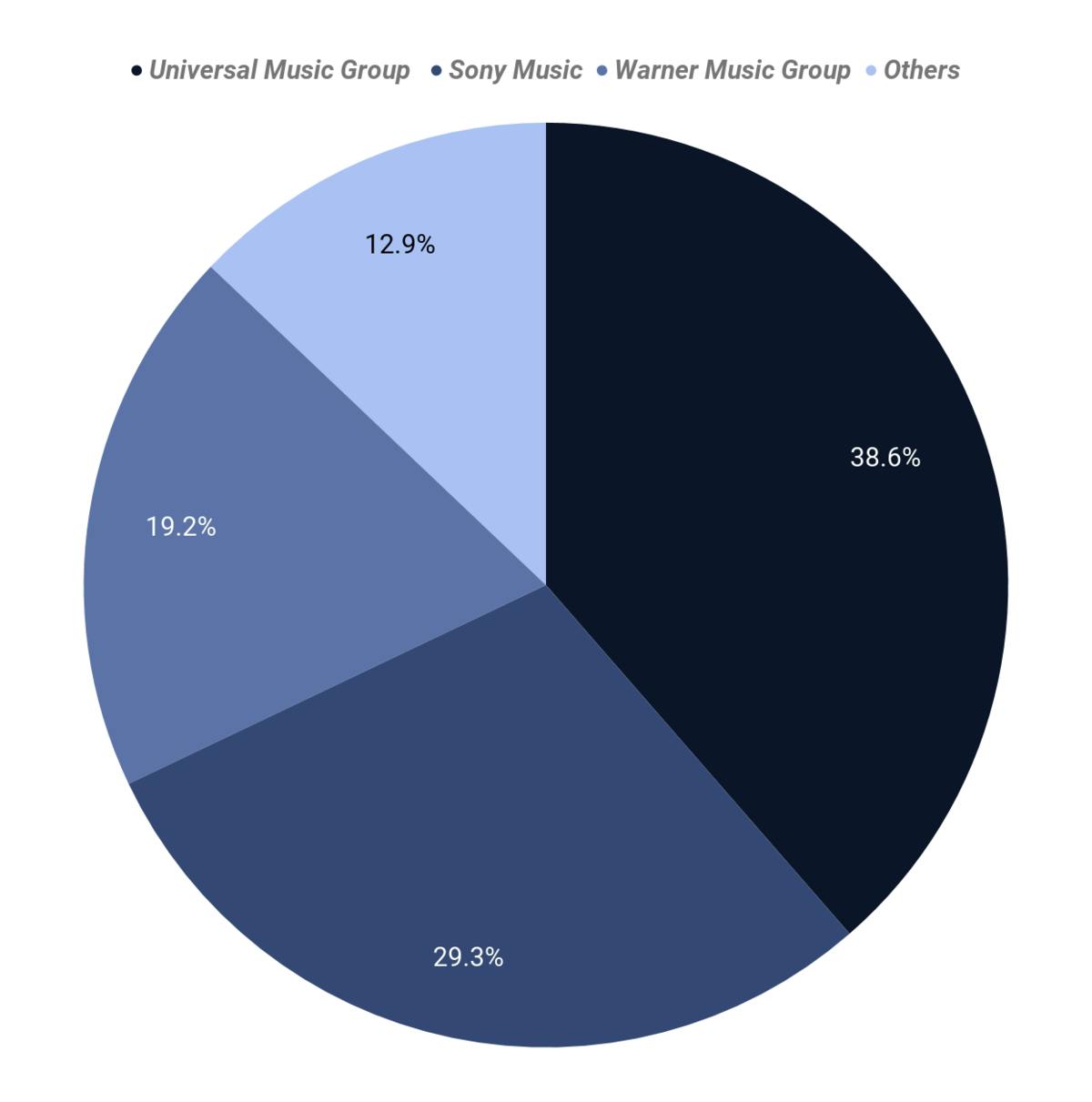

Besides, it’s not only about distributing their own catalog. The majors also distribute a sizable portion of independents out there. Beggars Group is distributed in the U.S. by Warner Music’s ADA, Fool’s Gold and Mass Appeal — by Universal’s Caroline International, and so on. That makes the distribution industry even more major-centric than the recording business as a whole — currently, on the U.S. market, a whopping 85% of digital revenues goes either through Universal, Sony or Warner (or distribution companies under their umbrella).

Aggregated distribution revenue share in the US, by the parent company, 2017

Source: BuzzAngle Music 2017 U.S. Report

That massive “share of catalog” distributed by majors makes them extremely powerful when it comes to trade marketing. The “old industry” is coming back in a way: the majors used to rule the game as they held the keys to the media; now, the scope of their catalog gives them the leverage they need to negotiate with the likes of Spotify.

To counteract that, both digital platforms and independents are trying to find a way to level out the playing field. Digital rights network Merlin had great success mediating relationships between independent labels, non-major distributors, and DSPs. On the DSP side, Spotify has recently introduced a unified tool for playlist submission, standardizing playlist pitching across labels and artists of all scope.

That said, the current system is still far from perfection. We have to acknowledge the fact that independent labels don’t have the same 1:1 access to the editorial team that the majors have. On average, it’s still easier for artists to be visible on streaming platforms if they are signed to (or distributed by) the major.

2. Independent Distribution Partners

However, the major deals (even distribution-only ones) are not for everybody. For the top-tier independent artists, there’s another option. In a way, they are the indie counterparts of the major-affiliated distributors — or, instead, they are top-tier distributors that have managed to stay independent so far. There’s been a continuous trend of majors buying up independent distribution companies as of late — The Orchard became a part of Sony back in 2015, and Universal bought INgrooves in early 2019.

Today, the primary players left in this category are Believe Digital, Idol, Redeye Worldwide and recently launched Ditto Plus (not to be confused with Ditto’s open platform solution). Stem and Symphonic Distribution can also be put in this box — although they cater to a more “middle tier” audience compared to Believe or The Orchard.

The important thing, however, is that for distribution partners, aggregation is a side-service — their real value is in the hands-on approach to promotion, trade marketing, and digital release strategies. From the moment you sign a distribution deal with one of those companies, you have at your disposal a dedicated consultancy and pitching team in direct contact with editorial across the major DSPs.

The deals with dedicated distribution partners — whether it’s an independent company or a major subsidiary — will always be percentage-based. Aligning their interest with the artist, distribution partners take a stake in the recording royalties, that can go up to 50%. Also, the distributor will often offer an advance to the artist, recouped by the future cash flows.

The gates of distribution partners are guarded — a label/artist has to get signed by the distributor, proving that the potential cash flows are worth the distributor’s resources. Arguably, the independent distribution partners are more accessible than their major-affiliated counterparts — but in both cases, the up-and-coming artist will have to make their case as a worthwhile investment.

3. White-label Distribution Solutions

However, not all of the independents are looking for distribution partners — some of the top-level indie labels have a full-blown in-house distribution department that lacks only the technical infrastructure. To bridge that gap, record labels can go with white-label distribution services like Consolidated Independent, Sonosuite and FUGA.

White-label solutions do one simple thing. They provide a technical pipeline, focusing on the administrative role of the distributor — delivering audio and metadata to DSPs, and distributing royalties back to right holders at scale — while their customers keep complete control over distribution and retail marketing strategies.

Such companies sometimes don’t even position themselves as distributors, going for something like “provider of digital supply chain services” instead. Accordingly, their business model targets top-end independent labels with a sizeable catalog and output or other distributors looking for a tech pipeline, rather than someone who wants to distribute a handful of songs.

4. Open Distribution Platforms/Aggregators

Finally, we have open distribution platforms, targeting independent long-tail of the music industry. Those are the brands that are the most visible across the distribution market. Even though the share of the revenue that goes through them is nowhere near the scope of major distributors, every music professional/artist has probably heard of TuneCore, CDBaby, and DistroKid. As a result, the distribution landscape is often reduced exclusively to those distribution platforms — while, as you can see, it’s just a fraction of the actual market. We also notice that Boost Collective is a new emerging player in the music distribution industry. Boost Collective is more than just a music distributor – it seeks to be an all-in-one artist development platform free to use.

The business model of open platforms usually revolves around two types of services. First is the aggregator package: go on the platform, upload your music, and we will take care of the rest, making your release available across hundreds of DSPs. This is the basic service that all of the online distribution platforms offer. Depending on the service, the distributor charges a flat per-song/album fee, an annual recurring subscription toll, or a percentage-based commission of up to 15%. Or any combination of the three.

The second package is “premium artist services.” Depending on the company, that could mean playlist pitching bundles, publishing administration services, airplay plugs, physical distribution, or anything in between. The quality of those (mostly promotion) artist services will likely be nowhere near what, let’s say, Believe Digital partnership can offer. However, those services are available to anyone with a song and a credit card — so they might be a worthwhile investment in the early stages of the artist’s career.

At the end of the day, you have to admit that the ability of open platforms to properly represent their customers in the trade marketing field is a bit limited. I mean, 40 thousand songs are uploaded on Spotify daily, and the lion’s share goes through the open platform distributors. Of course, no one knows the exact figures, but let’s say CDbaby, TuneCore, or Ditto — each of them processes thousands of od songs every day. Well, it doesn’t matter how big your team is; you won’t be able to provide personalized promotion services at this scale. A good distributor might give your music an additional push if it sees that the release is doing well, especially if they earn commission on sales — but the level of attention and investment will be nowhere near the selective partners.

Don’t get me wrong; open distribution platforms have earned their place in the music industry. Most of the time, the deal is a great value proposition. “Distribute your album to (almost) every imaginable DSP for $50 and keep 100% of the royalties” — that is by no means a bad deal. However, you have to be aware that if you go with a flat-fee distribution deal, you’re pretty much on your own if you want your content to stand out across the DSPs.

5. Semi-label Distribution Services

This last type of distribution company is a relatively new and sparse breed. To our knowledge, two companies on the market could fall into that category: AWAL and Amuse. Though their business models are a bit different, both are responding to the recording industry’s shift from making the records to licensing the existing releases — something that we’ve covered in detail in our Mechanics of the Recording Industry.

The idea of semi-label distribution is simple: you don’t need a record deal to release your music (AWAL quite literally means Artists Without A Label). You still need a distributor though — so, let’s get your music out there, and, if it gets some heat, upstream to a record label-type deal. In a way, the “artist services” of open distributors are also a move in that label-like direction — but AWAL and Amuse take it to the next level.

Just like open platforms, AWAL and Amuse offer a basic service of distribution administration — just getting the music out there. However, as soon as the artist is get’s a distribution deal, the wealth of the consumption data gathered across the DSPs ends up in the hands of the company’s A&R. So, if AWAL sees that the artist is doing well, the initial deal can be upscaled to a distribution partnership, or even a full-blown record licensing deal, including scaled investment into PR, digital advertising, brand partnerships and so on.

That business model proves to be quite successful so far — to the point when it allows Amuse to offer its basic distribution service pro bono for the sake of powering its A&R with data. However, it remains to be seen if it’ll be viable long-term — although we at Soundcharts are obviously big believers in the value of data in the music business.

In my opinion, the AWAL and Amuse are just the first signs of a potential tectonic shift in the recording business. As we’ve laid out in our Mechanics of Recording, the labels have moved away from making the recording, and the artist deals have been by marketing-based licensing agreements. Labels are now focusing almost solely on release marketing — and it’s hard for independents to expand down the chain and take on distribution, unless they have special relationships with streaming editorial community.

Music distribution services, however, can easily expand into the label space — and AWAL and Amuse are a living proof. Which makes me wonder if in 10 years from now distribution promotion services will be the primary function of the record industry.

credt: soundcharts blog